Introduction to Behaviorism

Behaviorism is one of those psychological theories that quietly shapes our daily lives, even if we don’t realize it. Every time you reward yourself after completing a task, stick to a routine because it “just works,” or respond automatically to a familiar situation, you’re brushing up against the core ideas of behaviorism. At its heart, behaviorism is a theory of learning that focuses entirely on observable behaviors rather than internal thoughts, emotions, or intentions. In simple terms, it argues that behavior is learned from the environment, and if you want to understand people, you should look at what they do—not what they say they feel.

This approach emerged as a reaction to earlier schools of psychology that relied heavily on introspection. Early psychologists asked people to describe their thoughts and feelings, but behaviorists believed this method was too subjective and unreliable. They wanted psychology to be a real science, grounded in measurable, observable data. So instead of asking “What are you thinking?”, behaviorists asked, “What happened before the behavior, and what happened after it?”

Think of behaviorism like watching a movie instead of reading the character’s diary. You may not know exactly what’s going on in their head, but by observing their actions and the consequences of those actions, you can predict what they’ll do next. That predictive power is what made behaviorism incredibly influential, especially in education, therapy, parenting, and even marketing.

In this article, we’re going to dive deep into behaviorism—where it came from, how it works, why it mattered so much, and why it still matters today. We’ll break down its core principles, explore famous experiments, and look at how behaviorism shows up in real life. By the end, you’ll have a clear, practical understanding of behaviorism and how this theory continues to shape human behavior in subtle but powerful ways.

Historical Background of Behaviorism

The story of behaviorism doesn’t begin in a psychology lab—it begins in philosophy. Long before psychology became a formal science, philosophers were already debating how humans learn and behave. Empiricists like John Locke argued that the human mind starts as a “blank slate,” shaped entirely by experience. This idea laid the groundwork for behaviorism, even though it wouldn’t fully emerge until centuries later.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, psychology was still trying to define itself as a scientific discipline. Early psychologists such as Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener relied on introspection, asking people to analyze and report their own thoughts. While innovative at the time, this approach faced criticism for being subjective and difficult to replicate. If psychology wanted to be taken seriously alongside biology and chemistry, it needed a more objective method.

Enter behaviorism. In the early 1900s, researchers began focusing on observable behavior—things that could be seen, measured, and quantified. Animal studies played a huge role here. Scientists noticed that animals could learn through repetition, rewards, and consequences, and they began to wonder: if animals learn this way, why not humans?

This shift marked a turning point. Psychology moved away from the mind as an abstract concept and toward behavior as a measurable phenomenon. Behaviorism quickly gained traction because it offered clear rules, predictable outcomes, and practical applications. From training animals to educating children, behaviorism promised a scientific way to shape behavior.

By the mid-20th century, behaviorism had become one of the dominant schools of thought in psychology. While it would later face criticism and competition from cognitive theories, its influence during this period was undeniable. To understand modern psychology, education, and even workplace management, you first have to understand this historical shift toward behaviorism.

Core Principles of Behaviorism

At its core, behaviorism is built on a few simple but powerful principles. The most important one is this: behavior is learned, not innate. According to behaviorists, we are not born with complex behaviors already programmed into us. Instead, we learn how to act through our interactions with the environment. Every experience, reward, and consequence plays a role in shaping who we become.

Another key principle is the exclusive focus on observable behavior. Behaviorists deliberately avoid speculating about internal mental states like thoughts, feelings, or motivations. Not because these don’t exist, but because they can’t be directly observed or measured. From a behaviorist’s perspective, if you can’t see it or measure it, it doesn’t belong in scientific psychology.

The environment plays a central role in behaviorism. Behavior is seen as a response to external stimuli. Something happens in the environment (a stimulus), and the individual reacts (a response). Over time, these stimulus-response connections become stronger or weaker depending on the consequences that follow. Positive outcomes strengthen behavior, while negative outcomes weaken it.

Behaviorism also emphasizes learning through conditioning. Whether it’s associating a sound with food or learning that hard work leads to rewards, conditioning explains how behaviors are acquired and maintained. This focus on learning made behaviorism especially useful in practical settings like classrooms, therapy sessions, and training programs.

In many ways, behaviorism treats behavior like a habit loop. Cue, action, consequence. Repeat the loop often enough, and the behavior sticks. This simple framework is one of the reasons behaviorism has had such a lasting impact, even as psychology has evolved to include more complex theories of the mind.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning is one of the most famous concepts in behaviorism, largely thanks to the work of Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov was a Russian physiologist who wasn’t even studying psychology when he made his groundbreaking discovery. He was researching digestion in dogs when he noticed something curious: the dogs began salivating before the food was presented, simply in response to cues associated with feeding.

Through careful experimentation, Pavlov demonstrated that a neutral stimulus, like the sound of a bell, could be paired with an unconditioned stimulus, such as food. After repeated pairings, the neutral stimulus alone was enough to trigger the response. The dogs learned to associate the bell with food, and their behavior changed accordingly.

This process became known as classical conditioning. It involves several key components:

- Unconditioned stimulus: Something that naturally triggers a response (food).

- Unconditioned response: The natural reaction to the stimulus (salivation).

- Conditioned stimulus: A previously neutral stimulus (bell).

- Conditioned response: The learned response to the conditioned stimulus.

Classical conditioning shows how behaviors can be learned through association. It helps explain everyday phenomena like phobias, emotional reactions, and even preferences. For example, if you had a bad experience while listening to a particular song, that song might trigger negative emotions long after the event itself.

In real life, classical conditioning happens constantly, often without us realizing it. Advertisers use it by pairing products with positive imagery. Teachers may unintentionally use it by associating certain subjects with stress or enjoyment. Once you understand classical conditioning, you start noticing how much of your emotional life is shaped by simple associations.

Operant Conditioning

If classical conditioning is about association, operant conditioning is about consequences. Developed by B.F. Skinner, operant conditioning explains how behaviors are shaped and maintained by reinforcement and punishment. Skinner believed that behavior is influenced by what happens after the action, not before it.

In operant conditioning, behaviors followed by positive outcomes are more likely to be repeated, while behaviors followed by negative outcomes are less likely to occur again. Skinner demonstrated this through experiments using animals, often placing them in what became known as the “Skinner box.” Inside the box, animals learned to press levers or perform actions to receive rewards or avoid discomfort.

Reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior, while punishment decreases it. This sounds simple, but the real power of operant conditioning lies in how precisely behavior can be shaped. By reinforcing small steps toward a desired behavior, complex actions can be taught over time—a process known as shaping.

Operant conditioning is everywhere. It’s in workplaces that reward performance with bonuses. It’s in schools that use grades and praise. It’s in parenting strategies that rely on consequences. Even social media uses operant conditioning, reinforcing engagement with likes, comments, and notifications.

Skinner’s work showed that behavior doesn’t need to be understood internally to be controlled externally. While this idea sparked controversy, it also provided practical tools that are still widely used today.

Types of Reinforcement

Reinforcement is one of the most practical and widely applied concepts in behaviorism. Simply put, reinforcement is anything that increases the likelihood that a behavior will happen again. What makes reinforcement so powerful is how naturally it fits into everyday life. From childhood through adulthood, our behaviors are constantly being shaped by reinforcement, whether we notice it or not.

There are two main types of reinforcement: positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement. Despite the confusing names, both are designed to strengthen behavior—not weaken it. Positive reinforcement involves adding something pleasant after a behavior, while negative reinforcement involves removing something unpleasant. In both cases, the goal is the same: encourage repetition of the behavior.

Positive reinforcement is probably the easiest to recognize. When a child gets praise for doing homework, when an employee earns a bonus for meeting targets, or when you treat yourself to coffee after finishing a difficult task, positive reinforcement is at work. The reward doesn’t have to be material; verbal praise, recognition, or even a sense of accomplishment can be powerful reinforcers.

Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, is often misunderstood. It does not mean punishment. Instead, it means removing an unpleasant stimulus to strengthen behavior. For example, fastening your seatbelt stops the annoying warning sound in a car. The removal of the sound reinforces the behavior of buckling up. Similarly, completing an assignment early to avoid stress later is another example of negative reinforcement.

Understanding reinforcement helps explain why habits form so easily—and why they can be so hard to break. Behaviors that are consistently reinforced tend to stick around. That’s why effective behavior change often starts with identifying what is reinforcing the current behavior and then adjusting those consequences strategically.

Types of Punishment

While reinforcement aims to increase behavior, punishment is designed to reduce or eliminate unwanted behavior. In behaviorism, punishment is any consequence that decreases the likelihood of a behavior occurring again. Like reinforcement, punishment comes in two forms: positive punishment and negative punishment. Again, “positive” and “negative” don’t mean good or bad—they refer to adding or removing something.

Positive punishment involves adding an unpleasant consequence after a behavior. A classic example is receiving a speeding ticket for driving too fast. The unpleasant consequence (the fine) is intended to reduce future speeding. In educational settings, extra assignments or reprimands are sometimes used as positive punishment, although their effectiveness is widely debated.

Negative punishment involves removing something desirable to reduce behavior. Taking away a child’s screen time for misbehavior or revoking privileges at work are examples of negative punishment. The loss of something valued makes the behavior less likely to occur again.

Although punishment can produce quick results, behaviorists have long warned about its limitations. Punishment doesn’t teach new or desirable behaviors—it only suppresses unwanted ones. In many cases, the behavior may return once the punishment is removed. Additionally, punishment can lead to fear, anxiety, or resentment, which may create new behavioral problems.

Modern applications of behaviorism tend to emphasize reinforcement over punishment. Encouraging positive behaviors often leads to more sustainable change than simply punishing negative ones. Still, understanding punishment is important, because it explains how authority, rules, and consequences shape behavior in societies, schools, and organizations.

Schedules of Reinforcement

One of the most fascinating aspects of behaviorism is the concept of reinforcement schedules. A schedule of reinforcement refers to how often and under what conditions reinforcement is delivered. Surprisingly, behaviors are often stronger when reinforcement is unpredictable rather than constant.

There are two broad categories of reinforcement schedules: continuous and partial (or intermittent). Continuous reinforcement occurs when a behavior is reinforced every single time it happens. This is effective for learning new behaviors quickly, but the behavior may disappear just as quickly when reinforcement stops.

Partial reinforcement involves reinforcing behavior only some of the time. This type of reinforcement leads to behaviors that are more resistant to extinction. Within partial reinforcement, there are several types:

- Fixed-ratio schedules, where reinforcement occurs after a set number of responses

- Variable-ratio schedules, where reinforcement occurs after an unpredictable number of responses

- Fixed-interval schedules, where reinforcement is given after a set amount of time

- Variable-interval schedules, where reinforcement occurs at unpredictable time intervals

Variable-ratio schedules are especially powerful. They’re the reason slot machines are so addictive. You never know when the reward is coming, so you keep going. Social media platforms also rely heavily on variable reinforcement—likes, comments, and notifications arrive unpredictably, encouraging constant engagement.

Understanding reinforcement schedules gives insight into why some habits are incredibly persistent. When rewards are unpredictable, behaviors become harder to break, which is both fascinating and a little unsettling.

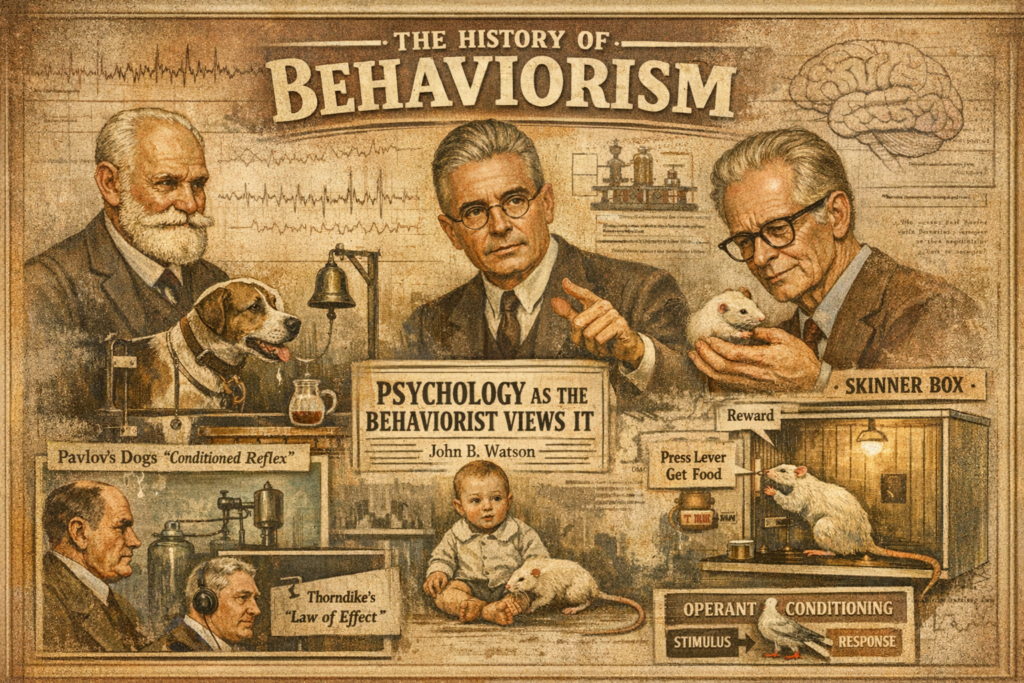

Major Behaviorist Theorists

Behaviorism didn’t develop overnight, and it wasn’t the work of just one person. Several influential theorists shaped the movement and refined its principles over time. Among the most important are John B. Watson, B.F. Skinner, and Edward Thorndike.

John B. Watson is often called the founder of behaviorism. He believed psychology should focus exclusively on observable behavior and reject introspection entirely. Watson famously argued that he could shape any child into any type of adult, given complete control over their environment. While extreme, this statement highlighted his belief in the power of learning and conditioning.

Edward Thorndike introduced the Law of Effect, which states that behaviors followed by satisfying outcomes are more likely to be repeated, while those followed by unpleasant outcomes are less likely to occur. This principle laid the foundation for operant conditioning and modern learning theory.

B.F. Skinner expanded on Thorndike’s ideas and developed a comprehensive theory of operant conditioning. Skinner rejected the idea of free will, arguing that behavior is determined by environmental consequences. His research and writing brought behaviorism into mainstream psychology and influenced education, therapy, and organizational management.

Together, these theorists transformed psychology into a more empirical and application-driven science. Even critics of behaviorism acknowledge that these thinkers fundamentally changed how we understand learning and behavior.

Behaviorism in Education

Few fields have been influenced by behaviorism as deeply as education. Behaviorist principles are woven into classroom management, curriculum design, assessment methods, and teaching strategies. At its core, behaviorism views learning as a change in observable behavior, shaped by reinforcement and feedback.

In the classroom, rewards such as grades, praise, stickers, or privileges are used to reinforce desired behaviors. Clear rules and consistent consequences help students understand expectations. Repetition and practice are emphasized to strengthen learning through reinforcement.

Programmed instruction, inspired by Skinner, breaks learning into small steps and provides immediate feedback. This approach can be seen in online learning platforms, language apps, and standardized test preparation tools. Each correct response is reinforced, encouraging continued engagement.

Critics argue that behaviorism oversimplifies learning by ignoring creativity, critical thinking, and intrinsic motivation. However, supporters point out that behaviorist strategies are highly effective for teaching foundational skills, managing classrooms, and supporting learners who need structure.

Even in modern, student-centered classrooms, behaviorism hasn’t disappeared. Instead, it has been integrated with cognitive and constructivist approaches, proving that its principles still have practical value.

Behaviorism in Psychology and Therapy

Behaviorism has played a major role in the development of therapeutic techniques, especially those focused on behavior change. Behavioral therapy aims to identify problematic behaviors and modify them through reinforcement, punishment, and conditioning.

One well-known application is Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), which is commonly used to support individuals with autism spectrum disorder. ABA focuses on breaking behaviors into smaller components and reinforcing positive changes consistently. While controversial, it has shown measurable success in improving communication and social skills.

Behavior modification techniques are also used to treat phobias, anxiety disorders, and addictions. For example, exposure therapy relies on principles of classical conditioning to reduce fear responses. By gradually exposing individuals to feared stimuli in a controlled environment, anxiety can be diminished over time.

Unlike insight-based therapies, behavioral approaches focus on action rather than interpretation. The goal is not to explore the past but to change present behavior. This practical focus makes behavioral therapy especially appealing in clinical settings where measurable outcomes are important.

Behaviorism in Everyday Life

Behaviorism isn’t confined to labs, classrooms, or therapy rooms—it’s everywhere. From morning routines to workplace dynamics, behaviorist principles quietly guide daily behavior. Habits, in particular, are a perfect example of reinforcement in action.

When you wake up and check your phone, the small hit of information or social interaction reinforces the behavior. When you stick to a workout routine because it makes you feel energized afterward, reinforcement is shaping your lifestyle. Even procrastination can be explained behaviorally—avoiding discomfort is negatively reinforcing.

Organizations use behaviorism through incentives, performance reviews, and goal-setting systems. Governments use it through laws, fines, and public policies. Marketers use it to influence consumer behavior by associating products with positive emotions.

Once you start viewing behavior through a behaviorist lens, patterns become obvious. You begin to see how much of what you do is shaped by consequences rather than conscious choice.

Criticism of Behaviorism

Despite its influence, behaviorism has faced significant criticism. One major limitation is its neglect of mental processes. Thoughts, beliefs, emotions, and intentions play a crucial role in human behavior, and ignoring them can lead to an incomplete understanding.

Critics also argue that behaviorism is too deterministic. By suggesting that behavior is entirely shaped by the environment, it downplays personal agency and free will. Humans are not machines, and behavior often involves creativity, insight, and internal motivation.

Additionally, behaviorism struggles to explain complex behaviors like language acquisition, problem-solving, and abstract thinking. These limitations led to the rise of cognitive psychology, which focuses on mental processes.

However, criticism doesn’t erase value. Instead, it highlights where behaviorism works best and where it needs support from other theories.

Behaviorism vs Other Psychological Approaches

Compared to cognitive psychology, behaviorism focuses on what people do rather than how they think. Cognitive approaches examine memory, perception, and reasoning, offering insight into internal processes that behaviorism ignores.

Humanistic psychology, on the other hand, emphasizes personal growth, self-actualization, and free will. It views humans as inherently good and motivated by internal drives, contrasting sharply with behaviorism’s external focus.

Each approach offers a different lens. Behaviorism excels at predicting and controlling behavior, while other theories provide depth and meaning. Together, they create a more complete picture of human psychology.

Modern Perspectives on Behaviorism

Today, pure behaviorism is rare, but its principles live on. Modern psychology often integrates behaviorist ideas with cognitive science, neuroscience, and social psychology. This blended approach recognizes both external behavior and internal processes.

Neo-behaviorism retains the emphasis on empirical research while acknowledging internal variables. Behavioral economics, habit research, and user-experience design all draw heavily from behaviorist concepts.

In a world driven by data, behaviorism’s focus on observable outcomes remains incredibly relevant. It reminds us that actions matter—and that change often starts with what we do, not just what we think.

Conclusion

Behaviorism may seem simple on the surface, but its impact is profound. By focusing on observable behavior and environmental influence, it reshaped psychology into a practical, measurable science. From education and therapy to habits and technology, behaviorist principles continue to shape the modern world.

While it has limitations, behaviorism offers powerful tools for understanding and changing behavior. When combined with other approaches, it becomes even more effective. Ultimately, behaviorism reminds us that small actions, repeated over time, can create meaningful change.

FAQs

1. What is behaviorism in simple terms?

Behaviorism is a psychological theory that explains behavior as learned responses shaped by the environment through reinforcement and punishment.

2. Who is the founder of behaviorism?

John B. Watson is considered the founder, while B.F. Skinner expanded and popularized the theory.

3. What is the difference between classical and operant conditioning?

Classical conditioning involves learning through association, while operant conditioning involves learning through consequences.

4. Is behaviorism still used today?

Yes, behaviorism is widely used in education, therapy, habit formation, and behavioral research.

5. What are the main criticisms of behaviorism?

Critics argue it ignores mental processes, emotions, and internal motivation, offering an incomplete view of human behavior.