Introduction to Abnormal Psychology

Abnormal psychology is one of those subjects that instantly sparks curiosity. After all, who hasn’t wondered why people think, feel, or behave in ways that seem completely different from what society considers “normal”? At its core, abnormal psychology is the branch of psychology that studies unusual patterns of behavior, emotion, and thought, which may or may not be understood as triggering a mental disorder. But here’s the thing—it’s not just about labeling people or putting them into neat diagnostic boxes. It’s about understanding the human experience in all its complexity, messiness, and vulnerability.

In today’s fast-paced, high-pressure world, abnormal psychology has never been more relevant. Anxiety disorders, depression, trauma-related conditions, and personality disorders are increasingly discussed in everyday conversations, social media, and workplaces. Mental health awareness campaigns have helped reduce stigma, but misunderstandings still exist. Many people assume “abnormal” means dangerous or broken, when in reality it often means someone is struggling to cope with internal or external stressors.

Abnormal psychology helps bridge the gap between misunderstanding and empathy. It provides frameworks to understand why someone might experience overwhelming fear, persistent sadness, distorted thinking, or extreme mood swings. More importantly, it guides clinicians, researchers, and policymakers in developing effective treatments and support systems. Think of it as a roadmap—it doesn’t define who a person is, but it helps us understand where they might be stuck and how they can move forward.

This field sits at the intersection of science and compassion. It combines biological research, psychological theories, and social insights to paint a fuller picture of mental health. And while the term “abnormal” may sound harsh, the ultimate goal of abnormal psychology is deeply human: to reduce suffering and improve quality of life.

Historical Evolution of Abnormal Psychology

To truly understand abnormal psychology, we need to take a step back in time. The way societies have explained unusual behavior has changed dramatically over centuries, often reflecting cultural beliefs rather than scientific evidence. In ancient civilizations, abnormal behavior was frequently attributed to supernatural forces. People believed that mental illness was caused by evil spirits, demonic possession, or divine punishment. Treatments were equally dramatic, ranging from exorcisms and rituals to trephination—a procedure where holes were drilled into the skull to “release” evil spirits. Sounds terrifying, right?

As we move into the classical Greek and Roman periods, a more naturalistic view began to emerge. Hippocrates, often called the father of medicine, proposed that mental disorders were caused by imbalances in bodily fluids, known as the four humors. Although his theory was incorrect by modern standards, it marked a crucial shift away from supernatural explanations and toward biological ones. Mental illness was seen as something to be treated, not feared.

Fast forward to the Middle Ages, and unfortunately, superstition made a comeback. Mental illness was once again associated with witchcraft and moral weakness. People with psychological disorders were often imprisoned, tortured, or ostracized. However, the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods slowly reintroduced reason and scientific inquiry. Reformers like Philippe Pinel in France and Dorothea Dix in the United States advocated for more humane treatment of individuals with mental illness, emphasizing care, dignity, and structured environments.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a turning point with the emergence of psychology as a scientific discipline. Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory introduced the idea that unconscious conflicts and early childhood experiences could influence behavior. While many of Freud’s ideas are debated today, his work laid the foundation for modern psychotherapy. Over time, behavioral, cognitive, biological, and humanistic approaches expanded the field, transforming abnormal psychology into the multifaceted science it is today.

Defining “Abnormal”: Key Concepts and Criteria

One of the trickiest questions in abnormal psychology is surprisingly simple: what does “abnormal” actually mean? There’s no single, universal definition, which is why psychologists rely on several criteria to evaluate whether a behavior or mental state is considered abnormal. These criteria help professionals make informed, ethical decisions rather than relying on personal opinions or cultural bias.

One common criterion is statistical infrequency. If a behavior or trait is extremely rare in the general population, it may be labeled abnormal. For example, experiencing hallucinations is statistically uncommon and often associated with psychological disorders. However, this criterion has limitations. High intelligence is also statistically rare, but we don’t consider it abnormal in a negative sense. Clearly, rarity alone isn’t enough.

Another important factor is deviation from social norms. Every society has unwritten rules about acceptable behavior. When someone consistently violates these norms—such as talking to themselves loudly in public or displaying extreme emotional reactions—it may raise concerns. The challenge here is cultural relativity. What’s considered normal in one culture might be seen as abnormal in another, so psychologists must tread carefully.

Personal distress is another key criterion. If a person experiences intense emotional pain, anxiety, or sadness that interferes with daily life, their experience may be considered abnormal. This is often the most compassionate measure because it centers the individual’s suffering. However, some disorders, like certain personality disorders, may not cause distress to the individual but still impact others.

Finally, maladaptive behavior refers to actions that interfere with a person’s ability to function effectively in society. This could include behaviors that are dangerous, self-destructive, or prevent someone from maintaining relationships or employment. When these criteria overlap, psychologists are more confident in identifying abnormal behavior. Together, they form a flexible framework rather than a rigid rulebook.

Major Theoretical Perspectives in Abnormal Psychology

Abnormal psychology isn’t built on a single explanation of mental disorders. Instead, it draws from multiple theoretical perspectives, each offering a unique lens through which to understand abnormal behavior. Think of these perspectives as different camera angles—each captures part of the picture, but none tells the whole story alone.

The biological perspective focuses on the brain, genetics, and neurochemistry. According to this view, mental disorders result from physical problems such as neurotransmitter imbalances, brain abnormalities, or inherited genetic vulnerabilities. For example, depression has been linked to serotonin dysregulation, while schizophrenia shows strong genetic components. This perspective has been instrumental in the development of psychiatric medications.

The psychodynamic perspective, rooted in Freud’s work, emphasizes unconscious conflicts and early childhood experiences. It suggests that unresolved internal struggles can manifest as anxiety, depression, or other disorders later in life. Although some aspects of this theory lack empirical support, its influence on talk therapy and self-reflection is undeniable.

Behavioral theories take a different approach, focusing on learned behaviors. From this perspective, abnormal behavior is acquired through conditioning, reinforcement, and observation. Phobias, for instance, can develop after a traumatic experience and persist because avoidance is negatively reinforced. Behavioral therapies aim to unlearn these maladaptive patterns.

The cognitive perspective highlights distorted thinking patterns. It argues that mental disorders arise from negative beliefs, irrational thoughts, and faulty assumptions about oneself and the world. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), one of the most effective treatments today, is based on this model.

Humanistic and sociocultural perspectives add yet another layer, emphasizing personal growth, self-worth, relationships, and cultural context. Together, these perspectives ensure that abnormal psychology remains holistic rather than reductionist.

Classification Systems in Abnormal Psychology

When it comes to understanding and treating mental disorders, classification systems play a crucial role. Imagine walking into a library where books aren’t organized by genre, author, or topic—total chaos, right? That’s exactly what the mental health field would look like without standardized classification systems. In abnormal psychology, these systems provide a common language for clinicians, researchers, and educators, helping them identify, diagnose, and study psychological disorders in a consistent and reliable way.

The most widely used classification system in the United States is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). Published by the American Psychiatric Association, the DSM serves as a comprehensive guide that outlines specific diagnostic criteria for hundreds of mental disorders. Each disorder is described in detail, including symptoms, duration, and severity thresholds. This helps clinicians avoid vague judgments and base diagnoses on observable and measurable patterns. For example, a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder requires a specific combination of symptoms lasting at least two weeks, rather than a general feeling of sadness.

On a global scale, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), published by the World Health Organization, is equally important. While the ICD covers all medical conditions, it includes a detailed section on mental and behavioral disorders. Many countries rely on the ICD for diagnosis, insurance, and health statistics. Although the DSM and ICD are largely aligned, subtle differences exist in terminology and categorization, which can influence diagnosis and treatment approaches.

Despite their usefulness, classification systems are not without criticism. Some argue that they medicalize normal human struggles, while others point out issues with cultural bias and overlapping symptoms across disorders. Still, these systems remain essential tools. They provide structure in a field that deals with incredibly complex and deeply personal human experiences, ensuring that abnormal psychology remains grounded in evidence-based practice rather than subjective interpretation.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychological conditions studied in abnormal psychology, affecting millions of people worldwide. While anxiety itself is a normal and even helpful emotion—it alerts us to danger and motivates preparation—anxiety disorders take this natural response and turn the volume all the way up. The fear becomes excessive, persistent, and difficult to control, interfering with everyday life.

One of the most prevalent anxiety disorders is Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). People with GAD experience chronic worry about a wide range of topics, from health and finances to relationships and work performance. This worry isn’t occasional—it’s constant, intrusive, and often accompanied by physical symptoms like muscle tension, fatigue, and restlessness. Imagine your mind running a never-ending “what if” loop that refuses to shut off, even when things are going well.

Panic Disorder is another significant anxiety-related condition. It’s characterized by sudden, intense panic attacks that can include heart palpitations, shortness of breath, dizziness, and a terrifying fear of losing control or dying. These attacks often come out of nowhere, which makes them even more distressing. Over time, individuals may begin to avoid places or situations where panic attacks previously occurred, leading to agoraphobia.

Phobias represent a more focused form of anxiety. Whether it’s fear of heights, spiders, flying, or medical procedures, specific phobias involve intense fear reactions to particular objects or situations. Social Anxiety Disorder, on the other hand, revolves around fear of social judgment and embarrassment. People may avoid speaking in public, attending gatherings, or even making phone calls. In abnormal psychology, anxiety disorders highlight how the brain’s survival mechanisms can misfire, creating fear where no real threat exists.

Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders form a unique category in abnormal psychology because they blend anxiety, cognition, and behavior in a powerful loop. At the center of this category is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), a condition marked by intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions). These obsessions are unwanted and distressing—think fears of contamination, harm, or moral failure. Compulsions, such as excessive handwashing or checking locks, are performed to reduce anxiety, but the relief is only temporary.

What makes OCD particularly challenging is that individuals often recognize that their thoughts and behaviors are irrational, yet they feel powerless to stop them. It’s like being trapped in a mental tug-of-war where logic loses to anxiety. Over time, OCD can consume hours of a person’s day, severely affecting work, relationships, and overall quality of life.

Other disorders in this category include Hoarding Disorder, where individuals struggle to discard possessions regardless of their value. This isn’t just messiness—it’s driven by intense emotional attachment and fear of loss. Living spaces can become unsafe, and relationships often suffer as a result. Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) involves an obsessive preoccupation with perceived flaws in physical appearance, flaws that are either minor or nonexistent. Individuals may spend hours checking mirrors, seeking reassurance, or avoiding social situations altogether.

From an abnormal psychology perspective, these disorders demonstrate how thought patterns can hijack behavior. Treatment often involves cognitive-behavioral strategies, particularly exposure and response prevention, which helps individuals confront their fears without engaging in compulsive behaviors.

Mood Disorders

Mood disorders are a central focus of abnormal psychology because they directly affect how people feel, think, and experience the world. Unlike everyday mood fluctuations, mood disorders involve persistent emotional states that significantly disrupt daily functioning. The most well-known mood disorder is Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), commonly referred to as depression.

Depression is far more than feeling sad. It’s a heavy, all-encompassing fog that affects motivation, energy, sleep, appetite, and self-worth. People with depression may lose interest in activities they once enjoyed, struggle with concentration, and experience feelings of hopelessness or guilt. In severe cases, thoughts of death or suicide may occur. Abnormal psychology seeks to understand depression through biological factors like neurotransmitter imbalances, as well as psychological and social contributors such as trauma, stress, and isolation.

Bipolar Disorders represent another category of mood disorders, characterized by extreme mood swings that range from depressive lows to manic or hypomanic highs. During manic episodes, individuals may feel euphoric, overly confident, and full of energy, often engaging in risky behaviors like excessive spending or reckless driving. These highs may seem productive or exciting at first, but they often lead to serious consequences.

Persistent Depressive Disorder, formerly known as dysthymia, involves a chronic, low-grade depression lasting for years. While symptoms may be less severe than major depression, their long duration can quietly erode a person’s sense of well-being. Mood disorders remind us that emotions are deeply tied to brain chemistry, life experiences, and cognitive patterns—all key areas of study in abnormal psychology.

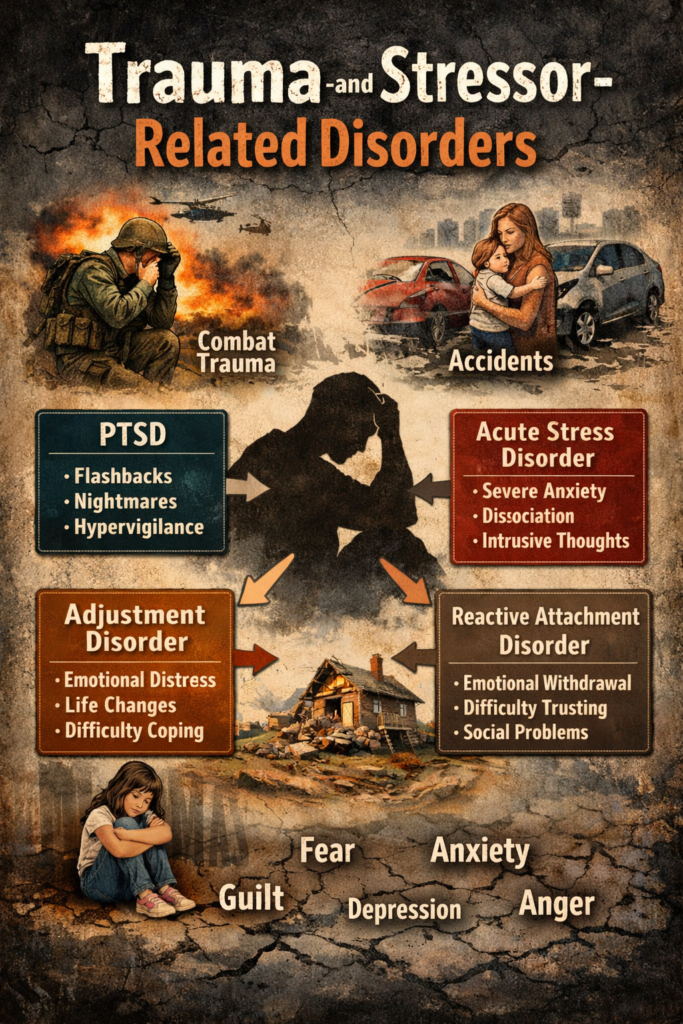

Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

Trauma has a profound impact on the human mind, and abnormal psychology devotes significant attention to understanding how extreme stress alters emotional and psychological functioning. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is perhaps the most well-known trauma-related disorder. It can develop after exposure to life-threatening events such as war, natural disasters, accidents, or assault.

PTSD symptoms typically fall into four categories: intrusive memories, avoidance, negative changes in mood and thinking, and heightened arousal. Flashbacks and nightmares can make individuals feel as though they are reliving the trauma, while avoidance behaviors may limit their ability to engage in everyday life. Hypervigilance, irritability, and sleep disturbances further compound the distress.

Acute Stress Disorder is similar to PTSD but occurs shortly after a traumatic event and lasts for a shorter duration. If symptoms persist beyond a month, the diagnosis may shift to PTSD. Adjustment Disorders involve emotional or behavioral reactions to identifiable stressors, such as divorce, job loss, or illness. While less severe, these reactions can still significantly impair functioning.

In abnormal psychology, trauma-related disorders highlight the brain’s attempt to protect itself after overwhelming experiences. Treatment often focuses on trauma-informed care, helping individuals process memories safely while rebuilding a sense of control and security.

Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

Few topics in abnormal psychology are as complex and misunderstood as schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. These conditions are characterized by a disconnect from reality, affecting perception, thought processes, emotions, and behavior. Schizophrenia itself typically emerges in late adolescence or early adulthood and can be profoundly disabling if left untreated.

Symptoms are often divided into positive and negative categories. Positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech—experiences that add something unusual to normal functioning. Negative symptoms involve reductions in normal behaviors, such as diminished emotional expression, lack of motivation, and social withdrawal. Cognitive impairments, including difficulties with memory and attention, are also common.

The causes of schizophrenia are multifaceted. Genetics play a significant role, but environmental factors such as prenatal complications, stress, and substance use also contribute. From a biological perspective, abnormalities in brain structure and dopamine regulation have been strongly implicated.

Other psychotic disorders include Schizoaffective Disorder, Delusional Disorder, and Brief Psychotic Disorder, each with distinct features and durations. Abnormal psychology emphasizes early intervention and long-term support, as timely treatment can dramatically improve outcomes and help individuals lead meaningful lives.

Assessment and Diagnosis in Abnormal Psychology

Assessment is the backbone of abnormal psychology. Without accurate evaluation, even the most advanced treatments can miss the mark. Psychologists use a combination of tools to gain a comprehensive understanding of an individual’s mental health. One of the most common methods is the clinical interview, which may be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured depending on the setting and purpose.

Psychological testing is another critical component. These tests can assess personality traits, intelligence, emotional functioning, and specific symptoms. Standardized instruments help ensure reliability and validity, allowing clinicians to compare results against established norms. Behavioral observation provides additional insights, especially in cases involving children or individuals with limited verbal communication.

Importantly, assessment is not about labeling—it’s about understanding. Abnormal psychology emphasizes differential diagnosis, ruling out alternative explanations such as medical conditions or substance use. Ethical considerations, cultural sensitivity, and informed consent are central throughout the assessment process, ensuring respect and accuracy at every step.

Treatment Approaches in Abnormal Psychology

Treatment in abnormal psychology is as diverse as the disorders it addresses. Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, remains one of the most effective interventions. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy helps individuals identify and change maladaptive thought patterns, while psychodynamic therapy explores unconscious conflicts and emotional insight. Humanistic approaches focus on self-acceptance and personal growth.

Medication also plays a vital role, particularly for conditions like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe depression. Antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers can significantly reduce symptoms when carefully prescribed and monitored. Increasingly, integrated approaches combine therapy, medication, and lifestyle interventions for holistic care.

Emerging treatments such as mindfulness-based therapies, neurostimulation techniques, and digital mental health tools are shaping the future of abnormal psychology. The goal is not just symptom reduction, but long-term well-being and resilience.

Conclusion

Abnormal psychology is more than the study of disorders—it’s the study of humanity under pressure. It helps us understand how biological vulnerabilities, psychological processes, and social environments interact to shape mental health. By exploring anxiety, mood disorders, trauma, psychosis, and beyond, abnormal psychology replaces fear and stigma with knowledge and compassion. In doing so, it empowers individuals, clinicians, and communities to move toward understanding, healing, and hope.

FAQs

1. What is the main focus of abnormal psychology?

Abnormal psychology focuses on understanding, diagnosing, and treating patterns of behavior, emotion, and thought that cause distress or impair functioning.

2. Is abnormal psychology only about mental illness?

No, it also examines resilience, coping strategies, and the continuum between normal and abnormal behavior.

3. How is abnormal psychology different from clinical psychology?

Abnormal psychology is more research-focused, while clinical psychology emphasizes assessment and treatment, though the fields overlap.

4. Can abnormal behavior be culturally relative?

Yes, cultural norms strongly influence what is considered normal or abnormal, making cultural context essential in diagnosis.

5. Are mental disorders treatable?

Most mental disorders are highly treatable with the right combination of therapy, medication, and support.